This is a preprint of: Ellerman, David. 2025. “The Historical and Modern Arguments Against Contractual Slavery.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Modern Slavery, edited by Maria Krambia Kapardis, Colin Clark, Ajwang Warria, and Michel Dion. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-58614-9_9.

Comments on the Danish EOT Law

The Danish EOT is an unworkable model for employee ownership and thus no solution for the growing problem of business succession. The failure of the model is analyzed in this paper.

Historical Copies of ICA Model By-Laws for a Worker Cooperative

These copies of the Industrial Cooperative Association (ICA) Model By-Laws go from an early version from the late 1970s to the mature version in the early 1980s. Also included are a report from the late 1980s on how to set up a democratic worker ownership trusts written for Zimbabwe plus a law journal article on the 1982 Massachusetts law on Employee Cooperative Corporations.

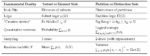

Marginal Productivity Theory versus Labor Theory of Property

This paper shows that MP theory can also be formulated in a mathematically equivalent way using vectorial marginal products–which however conflicts with the “distributive shares” picture.

On Employee Ownership Trusts (EOTs)

This paper explores the Employee Ownership Trust (EOT) model, comparing it with traditional partnerships and employee ownership structures like the US ESOPs and the European Coop-ESOPs.

Market Valuations are Inappropriate for Employee-Owned Firms

Any `fair market valuation’ of an employee-owned firm or partnership that assumes those future residuals accrue to the current shareholder/residual-claimants is inappropriate.

The Basic Ideas of Quantum Mechanics

For a century, quantum theorists have been reading the mathematical entrails of quantum mechanics (QM) to divine the nature of quantum reality. But to little avail. Let’s try a new approach.

The Mean and Variance as Dual Concepts

This paper gives a new derivation of the variance (and covariance) based on the two-sample approach, which positions the variance on the partition and information theory side of the duality and thus dual to the mean.

Generative Mechanisms

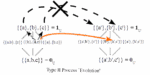

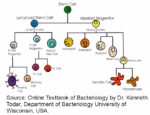

The purpose of this paper is to abstractly describe the notion of a generative mechanism

that implements a code and to provide a number of examples including the DNA-RNA machinery that

implements the genetic code, Chomsky’s Principles & Parameters model of a child acquiring a specific

grammar given ‘chunks’ of linguistic experience (which play the role of the received code), and embryonic

development where positional information in the developing embryo plays the role of the received code.