Introduction: Outline of the argument

The purpose of this paper is to suggest a rethinking of the common-versus-private framing of the property rights issue in the Commons Movement. The underlying normative principle we will use is simply the basic juridical principle that people should be legally responsible for the (positive and negative) results of their actions, i.e., that legal or de jure responsibility should be imputed in accordance with de facto responsibility. In the context of property rights, the responsibility principle is the old idea that property should be founded on people getting the (positive or negative) fruits of their labor, which is variously called the labor or natural rights theory of property [Schlatter 1951].[1]

For instance, the responsibility principle is behind the Green Movement’s criticism of the massive pollution and spoliation by corporations that don’t bear the costs or legal responsibility for their activities. Ordinary economics shows that markets do not function efficiently in the presence of these “negative externalities” but the responsibility principle shows that there is injustice (i.e., the misimputation of responsibility) involved as well, not just inefficiency, and that aspect is overlooked by conventional economics.

The current economic system institutionalizes forms of social irresponsibility that go far beyond the topic of negative externalities. Indeed, the forms of socialized irresponsibility embodied in Wall Street capitalism are behind the current economic crisis, although the roots are much older. In recent decades, the American model of Wall Street capitalism has been promoted as an “advanced” model of a market economy to be emulated not only in the industrialized countries but also in the post-socialist and developing worlds. Hence the current crisis provides the opportunity to finally discredit the idea that this “advanced” form of socialized irresponsibility should be emulated by anyone. That is the topic of the next section.

But our main point goes much deeper than just a tamed or reformed version of capitalism; it goes to the form of private property behind the system. The ideology of the current system seems to have convinced those on both the Left and Right that the current system is based on the principles of private property so that anyone who opposes the current system is an “enemy of private property” itself, as the Commons and Green Movements are often portrayed (and as some members of those movements may portray themselves). We will see that practically the opposite is true.

Like the old system of chattel slavery, the current property system is “a” private property system but it is grounded on violating the very responsibility principle upon which property appropriation and other juridical imputations are supposed to rest. And when private property is refounded on the responsibility principle (or the labor theory of property) then a very different system emerges where firms are worker cooperatives (or similar workplace democracies) where people will appropriate the positive and negative fruits of their labor. Moreover this refounding of property on the responsibility principle provides no basis to treat the products of nature as if they were ordinary private property.

The rethinking of private property will take place in two steps: (1) the undoing the “brain-washing” ideology that the usual form of enterprise is based on “private ownership of the means of production” and (2) the application of the responsibility principle to the human activities of the people working in any enterprise where they are inalienably de facto responsible for both the positive and negative results of their activities. After two sections on those two steps and a section on the notion of inalienability, we show how the corporation can be re-constituted from these first principles. Then we conclude with the negative application of the labor theory of property to the products of nature (natural resources) where some common ownership arrangement is required (rather than ordinary private ownership) so that the equal claims of future generations can be respected.

Wall Street capitalism as institutionalized irresponsibility

The market principle of responsibility

In the 20th century capitalism-socialism debate, it was always emphasized that markets embody a certain feedback loop between beneficial actions and rewards as well as between damaging actions and paying the costs of those actions. In short, markets are supposed to institutionalize the connection between actions and bearing the responsibility for those actions. When the connection breaks down (“externalities” in the language of economics), then markets malfunction.

Yet over the last century, there have been innovations, particularly in the type of market economy loosely identified as Wall Street capitalism, that have systematically institutionalized a disconnect between actions and bearing the consequences of those actions. The irony is that these innovations are not seen as some non-market interventions corrupting the market principle of connecting actions and responsibility. They have been seen as the creation of new “markets” heralded as “improvements” and “advances” in market economies. In the eyes of American leaders and pundits, these institutional innovations are supposed to be the envy of the world.

Institutionalized irresponsibility in “advanced” financial markets

The continuing American-caused economic crisis of 2008 was due in large part to a new set of financial instruments (derivatives) and the markets in those instruments. Derivatives were widely touted as innovative financial instruments that “could” be used to hedge risk in new ways. Of course, by the same token, derivative markets can be used to greatly increase risks (and rewards). As it turned out, the explosive combination of secondary markets in junk mortgages and derivatives markets created trillions of dollars of losses spread over the whole population, a population that had no responsibility for these Wall Street “innovations.”

The root of the problem cannot be solved by tweaking regulations. The basic problem goes back to the violation of the most fundamental norm of a market economy, the connection between actions and bearing the responsibility for the actions.

The “Model” of the absentee-owned publicly-traded corporation

The recent financial crisis is only a surface tsunami in comparison with slower and longer term tectonic shifts in the form of the large corporation due to Wall Street. The mother of all disconnects in the American or Anglo-Saxon model of a market economy is the absentee-owned corporation created by the public trading of the equity shares, i.e., by the set of market institutions collectively called “Wall Street.” The creation of public markets in corporate ownership shares was also seen as a great innovation, improvement, and advance in a market economy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Anglo-Saxon model, “the Stock Exchange is not the appendix or gall bladder of the body economic, but its very heart.” [Dore 1987, p. 118]

Yet these “new markets” created the most fundamental violation of the market principle of linking actions and their consequences, the violation that Berle and Means [1932] famously characterized as the separation of ownership and control. On a grand scale, corporate executives could, on the sole basis of their organizational role (like the nomenklatura of communism), make decisions that directly affected the people working in the companies (and indirectly their communities) without any responsibility mechanism to hold the decision-makers accountable. At least in a political democracy, there is in theory the responsibility mechanism of the voters “throwing the bums out.” But an absentee-owned company is not even an economic or workplace democracy in theory.[2] The people working in the large corporations, who are the people actually governed by the managers and who primarily bear the brunt of the decisions, have no vote in the matter.

And the so-called “owners” (the far-flung shareholders) have been so atomized by the wide distribution of shares by Wall Street that the usual difficulty of organizing collective action across the widespread shareholders prevents any effective use their voting power. The aptly-termed “Wall Street Rule” prevails; if you are dissatisfied with the company, then exit by selling the shares. No one buys shares on Wall Street thinking they will have any real influence on management; the shareholders are in fact only passive investors like bondholders. As was pointed out by John Maynard Keynes:

The divorce between ownership and the real responsibility of management is serious within a country when, as a result of joint-stock enterprise, ownership is broken up between innumerable individuals who buy their interest today and sell it tomorrow and lack altogether both knowledge and responsibility towards what they momentarily own. [Keynes 1933, 235-6]

In fact the only people in sight who the capacity and the incentive to monitor corporate management are the people working in the corporation. “The only cohesive, workable, and effective constituency within view is the corporation’s work force.” [Flynn 1973, 106]

Not all market economies have rushed headlong to imitate that “envy of the world,” Wall Street capitalism. The Japanese idea of the company-as-community [Dore 1987] is the basis for a fully competitive “employee-favouring” (as opposed to “shareholder-favouring”) model [Dore 2000]. Germanyhas also developed more responsible and even “employee-favouring” forms of enterprise. The German institution of Mitbestimmung [Dore 2000] is inconceivable in the American-style corporation which treats the livelihood of the people in the firm as a cost category to be minimized in whatever way possible. This includes moving the jobs to low-cost labor elsewhere—which has the added effect of slowly deindustrializing the country, devastating the economic base of whole regions, and slowly demolishing the middle class—all the while creating unimagined wealth for the few in control.

But until there is a rethinking of “private property,” even the modest steps towards a more participative and democratic model (e.g., the Japanese “employee-favouring” firm or German Mitbestimmung) will always be seen as “violating” private property rights and as retrograde vestiges that only impede the latest “innovations” in Wall Street capitalism that “should” be the envy of the world.

The fundamental brain-washing myth about private property

The medieval origins of the fundamental myth

The fundamental myth, accepted by both the Right and Left, is that the current economic system is founded on the “private ownership of the means of production” so that any basic changes would be a violation of “private property.”

The basic myth goes back to the old idea, prominent in the Middle Ages, that the governance or Lordship over people residing on and using the land was considered part and parcel of the Ownership of the land. As Maitland put it: “ownership blends with lordship, rulership, sovereignty in the vague medieval dominium,….” [Maitland 1960, 174] The landlord was the Lord of the Land. But then socialists and capitalists alike—each for their own reasons—carried over the idea that “Rulership and Ownership were blent” [Gierke 1958, 88] to the “ownership of the means of production.”

It is not because he is a leader of industry that a man is a capitalist; on the contrary, he is a leader of industry because he is a capitalist. The leadership of industry is an attribute of capital, just as in feudal times the functions of general and judge were attributes of landed property. [Marx 1977 (1867), 450-451]

Indeed, that bogus analogy is why the current system is called “capitalism.”

Note that the issue here is not whether the owner of property in land or capital has the legal right to exclude others and to make them trespassers if they use the property without the owner’s consent. The idea is that the ownership of land or capital carried with it the right of governance (in the case of land) or management (in the case of capital), and thus any alternative arrangement where the owners of land or capital were not in discretionary control would be a violation of those “property rights.” The Right uses this idea to defend the “capitalist” system, and the Left accepts the idea just as strongly and then concludes that these “private property rights” must be over turned in favor of the “social ownership” or “common ownership” of business enterprises. But, as we will argue:

- this idea that “Rulership and Ownership [are] blent” is a myth even in the current system,

- the current system is not based on the “private ownership of the means of production” but on the institution for the voluntary renting of human beings (the employment contract),[3] and

- when private property is refounded on applying the responsibility principle to the products of labor, which would entail abolishing the human rental contract, that automatically implies that enterprises would have to be restructured as worker cooperatives or some form of democratic firm.

Why the fundamental myth is only a (successfully brain-washed) myth

To see the fallacious nature of the myth, one only has to take a few seconds to consider the case where the ownership of the capital assets (e.g., machines, buildings, land, or other capital goods) stays the same but the assets are rented, leased, or loaned to another legal party who undertakes the productive process. Then the asset owner still has his ownership of the capital asset but has no ownership of the products or management rights over the process (which might include rented or leased assets from many owners). One would think this suppose-the-capital-is-rented-out argument would be easily available to people on the Right and Left who constantly use phases like “ownership of the means of production.” But the misuse of these phrases is ubiquitous and takes many different forms. Even if a person, perchance, understood the argument in one context, they may still make the same mistake in other contexts.

For instance, one way to state the point is that “residual claimancy”[4] is not a property right attached to the ownership of the “means of production”; residual claimancy is a contractual role determined by who hires what or whom in the marketplace. One would think that those who are much enamored with markets would take the trouble to understand the effects of market contracts. Those who unthinkingly talk about “ownership of the means of production” as if that ownership included residual claimancy are in effect acting like capital cannot be rented. But the characteristic feature of the misnamed “capitalist” economy we have today is not that capital cannot be rented—but that people can be rented.

In the earlier parallel development, as land became seen just as real estate property, the basis used to try to legitimate political Rulership became a contract of subjection.

Then, when the question about Ownership had been severed from that about Rulership, we may see coming to the front always more plainly the supposition of the State’s origin in a Contract of Subjection made between People and Ruler. [Gierke 1958, 88]

Similarly, the basis for capitalist production (where capital may be rented) is the contract of subjection for the workplace, the renting of the workforce in the employment contract.

Thus in this people-rental economy, the legal party that ends up “being the firm” in the sense of the residual claimant is determined by which way the rental or hiring contracts are made, e.g., by the owners of capital renting people, by people renting capital from its owners, or by some third party renting both the people and assets involved in a productive activity.

When stated in this simple way, it is relatively easy to get agreement that capital can be rented and thus that residual claimancy is determined by the pattern of contracts so “residual claimancy” is not “owned.” But then people will turn around and commit the fallacy in other ways—particularly when the legal party undertaking a productive activity is a corporation. Then they misinterpret the ownership of the corporation as automatically including the “ownership” of residual claimancy in any productive activity using the corporation’s assets—as if a corporation’s assets could not be rented or leased out.[5]

But the ownership of a real estate company that owns a mall does not include residual claimancy in the stores that operate in the mall. Or the ownership of an oil company or cab company does not include the residual claimancy in the operation of the gas stations or cabs leased to independent operators. Depending on the contracts, a corporation can be just the owner of assets leased to other operators or it can be the operating company using those assets in a productive activity. Thus the residual claimancy in the going concern that uses capital assets owned by a corporation is not part of the ownership of the corporation but depends on the pattern of market contracts.[6] And it might be emphasized again that this is not a normative argument about what property should be; it is an argument about the current private property system that it is only a myth that the product and management rights are part of the “ownership of the means of production.”

Common examples of the myth

Marx’s “ownership of the means of production,” indeed Marx’s notion of “capital,” which was used to misname the current system, was based on this fallacy. By “capital” Marx did not simply mean financial or physical capital goods (which Marx called the “means of labor”); he meant those goods used by wage labor with private ownership of the means of production and where the capital owner is the “firm” in the sense of being the residual claimant. Otherwise, “capital” becomes just the “means of labor.” In short,

Marx’s “capital” = “means of labor” + “contractual role of being the firm.”

If one wishes to use the word “capital” in that Marxian sense, then one gives up being able to talk about the “ownership of capital” since there is no “ownership” of the contractual role of being the residual claimant. But Marx continued to talk about “capital” (in the sense that includes residual claimancy) as being owned in a linguistic move that might be called a “semantic straddle” (i.e., an invalid argument based on using the same word with two different meanings in different parts of the argument).

There is a similar ambiguity in the common language notion of “owning a factory.” There is the ownership of factory buildings (and the ownership of corporations with such assets), but there is no “ownership” of the going-concern aspect of operating a factory as that is a contractual role in a market economy (residual claimancy). If the owner of a factory building leased it to an operating company, then the factory owner would not be the “firm” or residual claimant for the business being conducted in the factory. By using the same Janus-phrase “owning a factory” to straddle both meanings, one could seem to have an argument that the contractual role of operating a factory was “owned”:

“Owning the factory” = “Owning the factory building” + “contractual role of being the firm.”

For instance, when it is argued to many economists today that “owning the factory” (in the sense of operating it) is a contractual role, not an extra owned property right, the typical response is: “Yes, but it is that role which is called the ‘ownership’ role.” After thus using “ownership” to name a contractual role, they then straddle back to the old meaning and talk of “ownership” as a property right. If one wants to talk about the contractual role of residual claimancy as the “ownership role” then one loses the freedom to switch back to the other meaning of “ownership” as a property right. It is surprising hard for well-trained social scientists to resist this use of the same phrase with different meanings in the same “argument,” particularly when dealing with ideologically sensitive matters.

The misformulated capitalism-socialism debate

This confusion as to what is involved in the ownership of the “means of production” is crucial to the misframing of the whole capitalism-socialism debate. The socialist side of the debate believes in the misframing as vehemently as the so-called “capitalist” side so that it will support their desired socialist conclusion that any non-capitalist mode of production must involve social if not government ownership of the means of production.

Even the debate about workplace democracy is similarly misframed as being about “social” versus private ownership of the means of production. For instance, the Yugoslav notion of the self-managed firm was based on an utterly muddled notion of “social ownership.” Many who defend economic democracy [e.g., Dahl 1985] still see the conventional firm as being based on the muddled notion of “private ownership of the means of production” (rather than the contract to rent human beings). Since they see the governance and product rights as being part of that “private ownership of productive property,” they see a “conflict” with democratic principles—which they would resolve in favor of democratic principles. Thus the democratic socialist position wants to “socialize” those non-existent property rights—particularly in corporations that are so big that they are in some sense already “social.” Thus the misframed debate about whether residual claimancy should be privately or socially “owned” misses the point that it is not owned at all. Being the firm is a contractual role, and the key institution in the misnamed “capitalist” system is not the “private ownership of the means of production ” but the voluntary contract for the renting of human beings.

The real debate is not about “socializing” private property but about the abolition of not just the voluntary self-sale contract but also the voluntary self-rental contract in favor of firms that generalize the family firm and self-employed business person to a larger scale where all the people working in the firm are its legal members. Far from socializing private property, that would for the first time base the appropriation (and termination) of private property in the products of labor on the just basis of the juridical responsibility principle.

Refounding private property on the responsibility principle

The application to the products of labor

At least since the time humanity moved beyond primitive animism, it has been recognized that only persons can be responsible for anything. Things are not responsible agents; responsibility is always imputed back through an instrument to the human user. A basic function in seemingly any legal system is the determination in trials or other judgments as to who was in fact responsible for some misdeed so that the legal responsibility in terms of liabilities and penalties can be appropriately assigned. Responsibility works both ways; there is also the question of who was responsible for certain beneficial results. People should have the legal responsibility for both the positive and negative results of their deliberate actions, the “fruits of their labor.” The theory of property is concerned with correctly assigning those rights and liabilities whenever new property is produced and old property is consumed, used-up, or otherwise destroyed.

That responsibility principle is essentially primordial; John Locke did not invent it. But Locke is usually associated with explicitly applying that principle to the theory of property, particularly the questions of property creation. This is the Lockean principle of “getting the fruits of your labor.” The economic activities of production and consumption differ from exchange in that they inherently involve the initiation and termination of property rights; exchange does not. In production, the services of land, persons, and capital (to use the classical trinity) are the “inputs” that are used-up in the process of producing the products or “outputs” to be sold to the customers.

But there is a problem when production is organized under the employer-employee relationship as opposed to say a family farm or small artisan-operated workshop where people are working for themselves. All the human beings who work in a productive enterprise, working employers or employees, are jointly de facto responsible for using up all the inputs to the process, but none of those liabilities are legally assigned to the employees. Similarly that jointly responsible human activity produced the products or outputs, but none of the initial property rights to the produced outputs are assigned to the employees. Instead, the employees are legally treated as only the suppliers of one of the “inputs,” labor services, and thus they are only one of the “outside” parties to whom the liability for that used-up input is owned, a liability usually paid off as wages and salaries.

When all or the overwhelming number of the responsible human beings involved in a joint productive activity have zero legal liability for the used-up inputs and zero legal ownership of the produced outputs, then it is somewhat problematic to give an “account” for the activity in terms of the responsibility principle. Hence our liberal scholars and social scientists need some other way to completely reframe the question preferably without even mentioning the r-word “responsibility” or expressions like “fruits of one’s labor.” That is one important use of the fundamental myth previously analyzed. All is settled by the “ownership of the means of production” so there is no need to mention the r-word at all.[7]

The inalienability of responsible human actions

Now everyone knows that the responsibility for human actions cannot be transferred like a commodity. The simple example of a hired criminal emphasizes the de facto inalienability of responsibility. A hired killer might tell the judge that he “sold” his actions to his employer. He voluntarily agreed to “perform certain actions in return for agreed upon compensation” (the standard description of the labor contract), and that is the extent of his legal involvement. But the judge would no doubt be unmoved by this argument that the employer should have the sole legal responsibility. Of course, any contract to commit a crime is illegal but the hired killer is charged, along with his employer, with murder, not making an illegal contract.

When Ronald Coase described the hiring or renting of human beings as the “legal relationship normally called that of ‘master and servant’ or ‘employer and employee’,” he used a modern British law book on the employment relation. That law book explains the case of the hired criminal as follows:

All who participate in a crime with a guilty intent are liable to punishment. A master and servant who so participate in a crime are liable criminally, not because they are master and servant, but because they jointly carried out a criminal venture and are both criminous. [Batt 1967, 612]

When the venture “they jointly carried out” was not a criminous venture but an ordinary productive enterprise, then it is hard for our liberal scholars and social scientists to argue that employees suddenly become non-responsible instruments “employed” by their “employer.” But since the Right and Left agree on the fundamental myth, there is usually no mention of the institutionalized violation of basic responsibility principle (applied to the products of labor) that should be the foundation of the private property system and other legal imputations—just the usual head-butting between “social ownership” and “private ownership” of the means of production.[8]

The consent-versus-coercion misframing

Although our main focus is on property rights, it may be helpful to briefly mention the parallel analysis of contracts.

In addition to the fundamental myth, another basic misframing shared by the Right and Left is the framing of issues in terms of consent versus coercion. Then the Right takes the high moral stand in favor of consent and contract as opposed to systems based on inherited status, divine rights, patriarchy, or totalitarian coercion. “Legitimate government must be founded on the consent of the governed.” [Tomasi 2012, 5][9] And the Left accepts the framing but argues that some contractual institutions, like wage labor, are not “really” voluntary and are more akin to feudalism and slavery.

But here classical liberalism suffers from intellectual amnesia. From Antiquity down to the present, the sophisticated defenses of political autocracy and even individual slavery have been based on consent.

For instance, the codification of Roman law in Institutes of Justinian gave three ways slavery could be legitimate and all had the incidence of consent and contract. One was an explicit contract. Another was a case where a person had by their own actions committed a crime worthy of capital punishment (e.g., being a prisoner in a war againstRome) and who then voluntarily agreed in a plea bargain to a lifetime of slavery instead of the capital punishment. And the third rationale is where a child of a slave mother is raised for eighteen or so years using the food, clothing, and shelter provided by the master, and this debt needs to be paid off through work (all the while accumulating more debt to the “company store”) or some other payment that would be a buy-out or manumission from this debt peonage.

On the liberal idea of government based on the “consent of the governed,” the great legal scholar, Otto von Gierke showed that at least by the Middle Ages, “there was developed a doctrine which taught that the State had a rightful beginning in a Contract of Subjection to which the People was party…. Indeed that the legal title to all Rulership lies in the voluntary and contractual submission of the Ruled could therefore be propounded as a philosophic axiom.” [Gierke 1958, 38-40] For instance, where monarchy existed as a settled condition, then the sophisticated legitimation was not by Locke’s carefully chosen foil, the patriarchy of Filmer, or by the Church’s Divine Right, but by the implied contract of subjection that had been vouchsafed by the prescription of time.

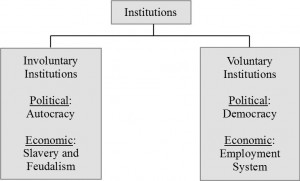

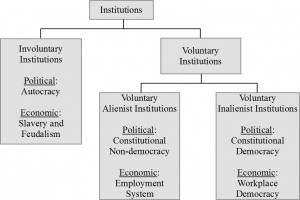

Since the sophisticated defense of all stripes of autocracy could be viewed as based on a social contract of subjection, the pactum subjectionis, what then is the defining characteristic of democracy that seems to escape our classical liberal scholars? The relevant distinction is not the contrast of coercion versus consent (or status versus contract etc.), but the distinction between:

1) contracts that alienate and transfer the right of self-government, and

2) contracts that only delegate authority to representatives to govern in the name of the governed.

Again Gierke traces this contrast between a pactum subjectionis and a democratic constitution.

This dispute also reaches far back into the Middle Ages. It first took a strictly juristic form in the dispute … as to the legal nature of the ancient “translatio imperii” from the Roman people to the Princeps. One school explained this as a definitive and irrevocable alienation of power, the other as a mere concession of its use and exercise. … On the one hand from the people’s abdication the most absolute sovereignty of the prince might be deduced, … . On the other hand the assumption of a mere “concessio imperii” led to the doctrine of popular sovereignty. [Gierke 1966, 93-94]

The civic republican scholar, Quentin Skinner, has emphasized the same contrast between alienation and delegation [1978]. Democratic theory is in fact based not on the courageous liberal stand against coercion and in favor of the consent of the governed nor on the critique of a pactum subjectionis as not being “really” voluntary. Democratic theory is based on a critique of the contracts of alienation as alienating that which is inalienable [Ellerman 2005, 2010b].[10]

The theory of inalienable rights descends from the Reformation (inalienability of conscience) and the Enlightenment through the abolitionist, democratic, and feminist movements to modern times. The basic idea is as simple as the consequences are profound. Due to the factual status as being mature person of normal capacity, people qualify for certain basic rights qua persons (or qua humans, if one prefers the human rights terminology). The argument was that any rights one has qua person are inalienable, even by a really voluntary contract and for whatever compensation, since after the contract is signed and “validated” by the legal authorities, then person still qualifies for the same rights on the same grounds qua person. Hence the pretended legal alienation was inherently invalid, and those qua-person (or qua-human) rights are inherently inalienable.

Of course, a legal system can still “validate” such a contract and count obedience to one’s master, sovereign, husband, or employer as “fulfilling” the contract, and then legally enforce the consequences in a type of legalized or institutionalized fraud. But as a result of the aforementioned social movements, voluntary self-sale contracts, nondemocratic pacts of subjection, and coverture marriage contracts have all been abolished in the advanced democracies. Only the system of human rental contracts remains.

Classical liberal thought has done its job well to get much of the Left to use the consent/coercion framing and to quibble about what is “really” voluntary (or whether the payment is big enough to compensate for all the “alienated labor-time”)—as if the whole institution for renting people would be acceptable if only people had other choices (like a guaranteed basic income) or were paid higher human rentals.[11]

This inalienable rights critique is not a choice in the liberal buffet because the contractual foundation for the governance of what most people do all day long, namely the employment contract, is an alienation contract. The employer is not the delegate, representative, or trustee of the employees and does not manage in the name of those managed. Hence the liberal insistence on the consent-versus-coercion framing is required so that the “legal relationship normally called that of ‘master and servant’ or ‘employer and employee’” [Coase 1937, 403] and political democracy will appear on the same side of consent-versus-coercion framing, whereas they are on the opposite sides of the alienation-versus-delegation framing (see previous diagrams).

Re-constituting the corporation from first principles

The responsible corporation

There have been a few—very few—social commentators who have pointed out the roots of the institutionalized irresponsibility in the absentee-owned joint stock corporation. In his 1961 book aptly entitled The Responsible Company, George Goyder quoted a striking passage from Lord Eustace Percy’s Riddell Lectures in 1944:

Here is the most urgent challenge to political invention ever offered to the jurist and the statesman. The human association which in fact produces and distributes wealth, the association of workmen, managers, technicians and directors, is not an association recognised by the law. The association which the law does recognise—the association of shareholders, creditors and directors—is incapable of production and is not expected by the law to perform these functions. [Percy 1944, 38; quoted in Goyder 1961, 57]

As indicated by Percy and Goyder, the basic solution is the re-constitutionalizing of the corporation so that the “human association which in fact produces and distributes wealth” is recognized in law as the legal corporation where the ownership/membership in the company would be assigned to the “workmen, managers, technicians and directors” who work in the company.

The bundle of corporate rights

We are now in a position to parse the rights involved in a corporation so that we may consider how the rights might be differently structured in a democratic firm based on first principles. We simplify down to the essentials: the voting rights (to elect the board to select the management and to vote on any other questions put to the owners/members) and the economic value rights which can now be parsed into the net asset value and the profits rights. The net asset value is for the current time but the voting and profit rights need to be broken down into the current rights and future rights after the current time period. Thus we have the following taxonomy:

Corporate Rights

A. Voting Rights

A.1. Current Voting Rights

A.2. Future Voting Rights

B. Value Rights

B.1. Profit Rights

B.1.a. Current Profit Rights

B.1.b. Future Profit Rights

B.2. Net Asset Value.

In the above taxonomy, it is the corporate rights which are being listed, not the non-existent rights to the “ownership” of residual claimancy (see earlier discussion of the fundamental myth). In the conventional joint stock company, these corporate rights (voting + value rights) are property rights represented by the common voting shares that may be owned and freely transferred as any other property rights.

The structure of rights in a democratic corporation

In a democratic firm such as a worker cooperative, the corporate ownership rights are not only rebundled but are assigned on a different basis. The voting rights are assigned on the basis of democratic principle of self-government. The people working in the firm are the only people under the management of the firm’s managers so by the democratic principle, the voting rights to elect those managers (perhaps indirectly through board election) should be assigned to the people working in the firm. Note that this assignment to those people is based on the assumption that those people are playing a certain functional role, i.e., working in the firm. They do not “own” the voting rights as property rights to be held or sold independently of their functional role. It is the same with voting rights in a political democracy. For instance, the voting rights in a democratic town or municipality are attached to the functional role of residing in the town or municipality.

We call rights assigned to a functional role personal rights. Where the entitling functional role is just being a person, then those personal rights are the basic human rights. In a democratic community of work or of residence, then the functional role is working in or residing in the community. In any case, such personal rights may not be sold as alienable property rights since the buyer may not have the entitling role, and if the “buyer” had the entitling role, then he or she would already have the rights on that basis.

The workers in the firm change so the assignment of the voting rights will change with the workforce. The future workers, like the future citizens in a political democracy, do not have to buy their voting rights from the present holders. Hence the separation of the (A) Voting Rights into the (A.1.) Current Voting Rights and (A.2.) Future Voting Rights. It is the (A.1.) Current Voting Rights that are part of the bundle of Membership Rights attached to the functional role of currently working in the democratic firm. The (A.2.) Future Voting Rights would be assigned when the future becomes the present.

The second normative principle, here called the responsibility principle, is just the standard jurisprudential norm of assigning to people the legal responsibility for the results of their deliberate and intentional actions. The intentional actions of the people working in the firm produce the outputs by using up the raw materials, intermediate goods, and the services of the durable goods in the firm. In net terms, the revenue from the outputs minus the non-labor costs for the inputs is the net valued added which can be parsed as: wages + profits. That is the net value of the assets (outputs) and the liabilities (for non-labor inputs) that the people working in a firm are jointly de facto responsible for producing. Hence by the responsibility principle, they should legally appropriate those assets and liabilities and thus receive the net value added. Since they already receive the wages, the additional value accruing to the people in a democratic firm is the (B.1.a.) Current Profit Rights. Thus those rights would also be in the bundle of membership rights assigned as personal rights to the functional role of working in the firm. As one might expect, the (B.1.b) Future Profits Rights represent the future positive and negative products that would be assigned to the future workers who produce them.

Thus on the basis of the first principles of democracy and private property (responsibility), we have accounted for all the rights except the (B.2.) Net Asset Value rights.

Current workers will, to be sure, use up the capital services derived from the company’s assets and that is why they are held legally responsible for those liabilities, but we are now concerned with the rights to the net asset value. This value represents property assets and liabilities accumulated in the firm by production and exchange activities in the past.

The system of internal capital accounts, pioneered by the Mondragon cooperatives [Ellerman 1990], is the means of keeping track of that history in a democratic firm so that the net asset value is owed in varying amounts to current and past members. They contributed to that value through any membership fees paid in and through any profits (or losses) retained in the firm rather than being paid out (or assessed in the case of losses). These claims could be thought of as a form of “internal” debt (like a shareholder’s loan) subordinate to all other (external) debts. Indeed, the internal capital accounts should be interest bearing. Those net asset rights (B.2.) are property rights, not personal rights. One litmus test to distinguish personal and property rights is inheritability. If a member dies, the voting and profit rights (like political voting rights) do not pass to the person’s estate, but the internal capital account balance would be a debt of the company to the estate of the deceased member.

Parsing the rights in capitalist and democratic corporations

|

Rights Structure |

Capitalist Corporation |

Democratic Corporation |

|

Current membership rights (A.1. + B.1.a.) |

Owned as property rights by shareholders |

Assigned as personal rights to the current workers |

|

Future membership rights (A.2.+B.1.b) |

Owned as property rights by shareholders |

Assigned as personal rights to the future workers |

|

Net Asset Value rights (B.2.) |

Owned as property rights by shareholders |

Owned as property rights by the current workers. |

Thus we have seen how all the corporate ownership rights are rebundled and assigned in a democratic firm. The current voting and profit rights are bundled together as the membership rights attached to the functional role of working in the firm (in practical terms, usually after a certain probationary period) so the future voting and profit rights would go to future members, and the remaining net asset value rights are captured in the system of internal capital accounts held by the current members. The rights structure in the so-called “capitalist corporation” and the democratic corporation can now be compared point-by-point in the table.

One important thing to notice is that in the democratic firm, the whole notion of the “ownership” of the company has evaporated. The old debate between private and social ownership of companies has been reframed. It is precisely the application of the private property principle to the products of labor that entails the company (implementing that responsibility principle) cannot itself be property. The membership rights are personal rights, not property rights, so a democratic company cannot itself be property. Similarly a democratic town or municipality may own property but is not itself a piece of property.

Hence we have finally arrived at an analysis very different from the usual treatment of privately owned conventional firms versus worker cooperatives or democratic firms. The democratic firm is a democratic human organization, and it is quite muddled and misleading to describe it as a piece of property that is socially or commonly owned. And its “non-ownership” follows from the private property (responsibility) principle applied to the products of labor.

Commonly owned resources: a negative application of the responsibility principle

We have so far applied the responsibility principle to the (positive and negative) fruits of the inalienably de facto responsible activities of the people working in a productive enterprise, i.e., to the products of labor.

But much of our world is not the products of labor but is the common endowment of nature. Hence the basic responsibility principle does not imply that such natural resources and endowments be treated as the private property.

The essential principle of property being to assure to all persons what they have produced by their labour and accumulated by their abstinence, this principle cannot apply to what is not the produce of labour, the raw material of the earth. [Mill 1970, 380]

No man made the land. It is the original inheritance of the whole species. Its appropriation is wholly a question of general expediency. [Mill 1970, 384]

Land might be represented as a durable asset yielding a stream of services now and throughout the future. When land and natural resources are privatized as ordinary private property, then it is not just the right to current services that is sold but the rights to all future services—which disenfranchises the future generations with an equal claim as the current generation. That is the basic idea behind the notion of “sustainable” use, i.e., use that would not prejudice the equal claim of future generations to the endowments of nature.

Even though land is not the fruits of anyone’s labor, the using up of the current services of land and of natural resources is part of the negative fruits of the labor of those who farm, mine, or otherwise use the land and resources. Thus the responsibility principle implies that those private parties should hold the liabilities for using up the current land services or resources. But the responsibility principle does not determine any private party to whom the liabilities should be owed.

Hence (1) the claims of future generations to future services and resources, and (2) the lack of a determinate private prior owner to current services and resources, both call for special common ownership arrangements for natural resources [e.g., land trusts or sky trusts, Barnes 2006] different from private ownership in the products of labor.

Our point here is that this rationale for common property-compatible arrangements follows from a negative application of the principle on which private property is supposed to rest since “No man made the land.”

Note that this analysis is quite different from an analysis calling for some collective property arrangement based solely on the characteristics of the property in question such as the common-pool resources where users subtract from the availability to others but it is difficult to exclude users [Ostrom 1990]. “No man made the land” but land is a “private good,” not a common pool resource by its exclusion/subtractability characteristics.

Concluding remarks

We have argued that on the key issue of property rights, the Commons Movement should not replay the 20th century’s juxtaposition of private-versus-social property (substituting “common” for “social”). “Private property” won that debate, but the root problems of irresponsibility remain. And few think an answer lies in recreating the 20th century’s notion of socialism. The issues need to be rethought from the ground up.

All concepts relating to the green economy place the economic sphere at the centre of any debate on future viability. According to this view, we can only save the planet with the economy, not against it. So do all solutions revolve around Homo oeconomicus once again? If we are looking for new models for society that accept human rights, equity, cultural diversity and democratic participation as fundamental principles while at the same time aiming to stay within ecological limits, we are tasked with nothing less than reinvention of the modern age. [Unmüssig, et al. 2012, 37]

We have suggested such a fundamental rethinking of the property rights issue. The current dominant economic system is in fact based on a violation of the principle on which private property is supposed to rest. When private property is refounded on a just foundation, then economic enterprises would be re-constituted as democratic firms such as worker cooperatives that are democratic human organizations (not pieces of property to be privately or socially owned).

Re-constituting firms as workplace democracies would reverse the mother of all disconnects, the absentee ownership of companies on the stock market, that has institutionalized the cancer of social irresponsibility on an unprecedented scale, as exemplified in the American form of Wall Street capitalism. With people empowered in their own enterprises, they would then be able to follow their natural self-regard not to foul their own nests and their natural social sympathies to sustain their own communities.

And with private property refounded on its proper role of guaranteeing the products of labor, then property arrangements other than ordinary private property are required to treat the products of nature in a manner that would recognize the equal claim of future generations.

References

Barnes, Peter 2006. Capitalism 3.0: A Guide to Reclaiming the Commons.San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Berle, Adolf and Gardiner Means 1932. The Modern Corporation and Private Property.New York: MacMillan Company.

Dahl, Robert 1985. Preface to Economic Democracy.Berkeley:University ofCalifornia Press.

Dore, Ronald 1987. Taking Japan Seriously.StanfordCA:StanfordUniversity Press.

Dore, Ronald 2000. Stock Market Capitalism: Welfare Capitalism. Japan and Germany versus the Anglo-Saxons.Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

Ellerman, David 1990. The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm. London: Unwin-Hyman Academic. All my references downloadable at: www.ellerman.org

Ellerman, David 1992. Property & Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy.CambridgeMA: Blackwell.

Ellerman, David 2005. Translatio versus Concessio: Retrieving the Debate about Contracts of Alienation with an Application to Today’s Employment Contract. Politics & Society. 33: 449-80.

Ellerman, David 2010a. Marxism as a Capitalist Tool. Journal of Socio-Economics. 39 (6 December): 696-700.

Ellerman, David 2010b. Inalienable Rights: A Litmus Test for Liberal Theories of Justice. Law and Philosophy. 29 (5 September): 571-599.

Fischer, Stanley, Rudiger Dornbusch and Richard Schmalensee 1988. Economics.New York: McGraw-Hill Co.

Flynn, John J. 1973. Corporate Democracy: Nice Work if You Can Get It. In Corporate Power in America. Ralph Nader and Mark J. Green ed., New York: Grossman Publishers: 94-110.

Gierke, Otto von 1958. Political Theories of the Middle Age. Trans. F. W. Maitland,Boston: Beacon Press.

Gierke, Otto von 1966. The Development of Political Theory. Trans. B. Freyd,New York: Howard Fertig.

Goyder, George. 1961. The Responsible Company. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Keynes, John Maynard 1933. National Self-Sufficiency. In The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes. Donald Moggeridge ed., London: Cambridge University Press: 233-46.

Maitland, F.W. 1960. Frederic William Maitland: Historian.Berkeley:University ofCalifornia Press.

Marx, Karl 1977 (1867). Capital (Volume I). Trans. B. Fowkes,New York: Vintage Books.

Mill, John Stuart 1970 (1848). Principles of Political Economy. Edited by Donald Winch. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Ostrom, Elinor 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action.New York:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Percy, Eustace. 1944. The Unknown State: 16th Riddell Memorial Lectures. London:OxfordUniversity Press.

Samuelson, Paul 1976. Economics.New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schlatter, Richard 1951. Private Property: The History of an Idea.New Brunswick:RutgersUniversity Press.

Skinner, Quentin 1978. The foundations of modern political thought. Volume Two: The Age of Reformation.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Tomasi, John 2012. Free Market Fairness. Princeton:PrincetonUniversity Press.

Unmüssig, Barbara, Wolfgang Sachs and Thomas Fatheuer 2012. Critique of the Green Economy: Towards Social and Environmental Equity.Berlin: Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Zimmern, Alfred E. 1918. Nationality & Government.London: Chatto & Windus.

[1] The labor theory of property is sometimes confused with the deeply fallacious “labor theory of value,” a confusion that is completely sponsored by the apologists for the current system of property so they can easily criticize the labor theory of property. [Ellerman 2010a]

[2] ”The manager in industry is not like the Minister in politics: he is not chosen by or responsible to the workers in the industry, but chosen by and responsible to partners and directors or some other autocratic authority. Instead of the manager being the Minister or servant and the men the ultimate masters, the men are the servants and the manager and the external power behind him the master. Thus, while our governmental organisation is democratic in theory, and by the extension of education is continually becoming more so in practice, our industrial organisation is built upon a different basis.” [Zimmern 1918, 263] And “shareholders’ democracy” is like having the people ofRussia “democratically” elect the government ofPoland.

[3] The use of the phase “renting people” instead of saying “hiring or employing people” is non-standard and is intended to get people to think anew about the institution. But it is not part of the controversy. According to the standard texts: “Since slavery was abolished, human earning power is forbidden by law to be capitalized. A man is not even free to sell himself: he must rent himself at a wage.” [Samuelson 1976, 52 (emphasis in original)] Or “We do not have asset prices in the labor market because workers cannot be bought or sold in modern societies; they can only be rented. (In a society with slavery, the asset price would be the price of a slave.)” [Fischer, et al. 1988, 323] Americans say “rental car” and the British say “hire car” but they are talking about the same thing. A rented person is a hired person, i.e., an “employee.”

[4] The residual or profit is the difference between the revenue and expenses in a business enterprise.

[5] This is a conceptual point that has nothing to do with the bargaining power or transaction costs involved in renting capital out of a corporation.

[6] Economists can understand this simple point about residual claimancy, at least for a few minutes until they turn to finance theory (and capital theory). Finance theory, currently a hot topic, as well as the older capital theory are based on definitions that capitalize the future value of the profits that result from residual claimancy into the current value of the capital asset (typically a corporation) even though the market contracts that amount to residual claimancy have hardly been made now for the entire future time periods. Hence there is no present property right to those future profits and thus that capitalized value cannot be added to the “value of the corporation” (or other capital asset) as if it were currently owned by the capital owners. This is spelled out in more detail in a blog entry [or Ellerman 1992]. Thus economists can understand the point in some non-threatening contexts, but the point is “unavailable” in other important and ideologically sensitive contexts, finance theory and capital theory, where economists are called upon to fulfill their social role of giving a “scientific account” of the current system.

[7] Try to find the r-word in the treatment of production in any economics textbook.

[8] For a book-length treatment of the labor theory of property and related questions, see Ellerman 1992.

[9] Tomasi [2012] may be used as a representative and recent restatement of classical liberal thought.

[10] The disconnect between classical liberal thought and democracy is clearly visible in the debate on charter cities or “free cities” which are newly built cities run by a foreign country, a corporation, or a group of rulers where people would indicate their consent to alienate their self-governance rights by voluntarily moving there and where they are free to leave at any time. The disconnect is shown by the strong libertarian support for such nondemocratic municipal governments like in old Hong Kong or modernDubai.

[11] “One can even say that wages are the rentals paid for the use of a man’s personal services for a day or a week or a year. This may seem a strange use of terms, but on second thought, one recognizes that every agreement to hire labor is really for some limited period of time. By outright purchase, you might avoid ever renting any kind of land. But in our society, labor is one of the few productive factors that cannot legally be bought outright. Labor can only be rented, and the wage rate is really a rental.” [Samuelson 1976, 569]