TITLE PAGE

INTRODUCTION

GLAGOLITIC PAST

1483 MISSAL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

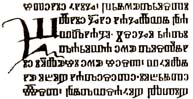

A page from the 1483 Missal (Krader 1963, p. 97).

Touched-up letter type (U), enlargement 12x (Paro 1997, p. 51).

Cutting in at the body of the type, at the intersection of verticals to create space for bleeding of the ink (Paro 1997, p. 55).

TYPOGRAPHY

The 1483 Missal was printed in the square form of the Glagolitic uncial script. Although the Missal of Prince Novak was used as the textual exemplar, the shape of letters and ligatures in the incunabula do not match one in the manuscript (Orešković 1969, p. 233).

The Missal was printed with two font sizes (bigger and smaller) and set of “small” initials. The smaller fonts were used for antiphonal parts: introitus, gradual, offertories and communion. The prayers, reading and other text were printed in type of the larger size. Together with the ligatures, abbreviations and 6 special signs (crosses, paragraph endings, periods …) it used 201 different signs (stamps). The set of “small” in-line initials is made of thirty signs (Bošnjak 1970, p. 159).

In its visual appearance the Glagolitic script is very similar to the gothic textura. And like textura, if the Glagolitic letters are written closely together to save the space, the letters tend to visually blend together and are difficult to read. What makes the type cutter of letters for the 1483 Missal master of his trade is his solution for this problem.

When looking at the straight lines, by optical illusion, verticals seems to narrow in the middle. The Greeks architects are the first, that we know, that started to use entasis—a slight convexity or swelling of the columns—to compensate for the visual illusion. However, this trick of the eye could be used to open a squat square letters like the Glagolitic one. By purposefully thinning the hast of the letters in the middle, letters visually open and are easier to read. The elegant line of Roman capitals is achieved by the narrowing of their verticals and serif stroke at the ending.

Analysis of the fonts used in the 1483 Missal shows that hasts were purposefully curved; wide, heavy letters are narrower, and thin letters wider than pure mathematical formula of the letter forming would require. The font that appears full of straight lines and sharp corners, under magnification show very few completely straight lines. Printed together in line they are as readable as any of the Latin humanistic fonts developed during that period.

Not only are the fonts an art-work of typographical design, they also show the profound understanding of the technological problems in the printing process. Traditionally, ink is applied to the surface of type with the pair of ink balls. They are fairly soft and tend to overink the type. When a forme is pressed, ink is forced over the edge of type which results in smudging of imprints of individual letters. This is further exuberated by the roughness of paper and uneven pressure of a platen. To compensate for that, type cutter of 1483 Missal cut off some metal on the crossings, where lines of the letter intersect, creating space for the ink to bleed in. That creates sharper corner, and minimizes the blotting in of the oval parts of the letters and creates cleaner and sharper imprint (Paro 1997, p. 41-59).

PRINTING

PRINTING

TEXT

TEXT

DESCRIPTION

DESCRIPTION

BINDING

BINDING

COPIES

COPIES

Bibliography

Bošnjak, M. (1970). Slavenska inkunabulistika. Zagreb: Mladost.

Bošnjak, M. et al. (1963). Vodeni znakovi hrvatskih inkunabula. Bulletin Zavoda za likovne umjetnosti JAZU, XI(3), 20-50.

Orešković, M. (1969). Osnutak i djelatnost glagoljaških štamparija u 15. stoljeću. Bibliotekar, XXI(2), 226-241.

Paro, F. (1997). Typographia Glagolitica. Zagreb: Matica Hrvatska.

Written by Vlasta Radan.

Last update April 10, 2006.